NOW SHOWING

On the ground floor, 35,000 Years to Catch a Shadow: A Reflective Exhibition challenges visitors to explore the Phenomenon, Arts, and Technologies of the Shadow.

Our latest exhibition, Production Design: Film’s Most Invisible Art features unique and rare original and donated materials from Oscar-winning designer Terence Marsh (the curator’s father), his mentor John Box, his friends, and his British design contemporaries – who have set a proud mark on Hollywood and worldwide design since the renaissance of the British cinema during and immediately after the Second World War.

World War One on Film and in the Media: Representation & Remembrance, Art & Authenticity, begins in the hallway, and travels upstairs into the lobby, Front Room and Viewing Room.

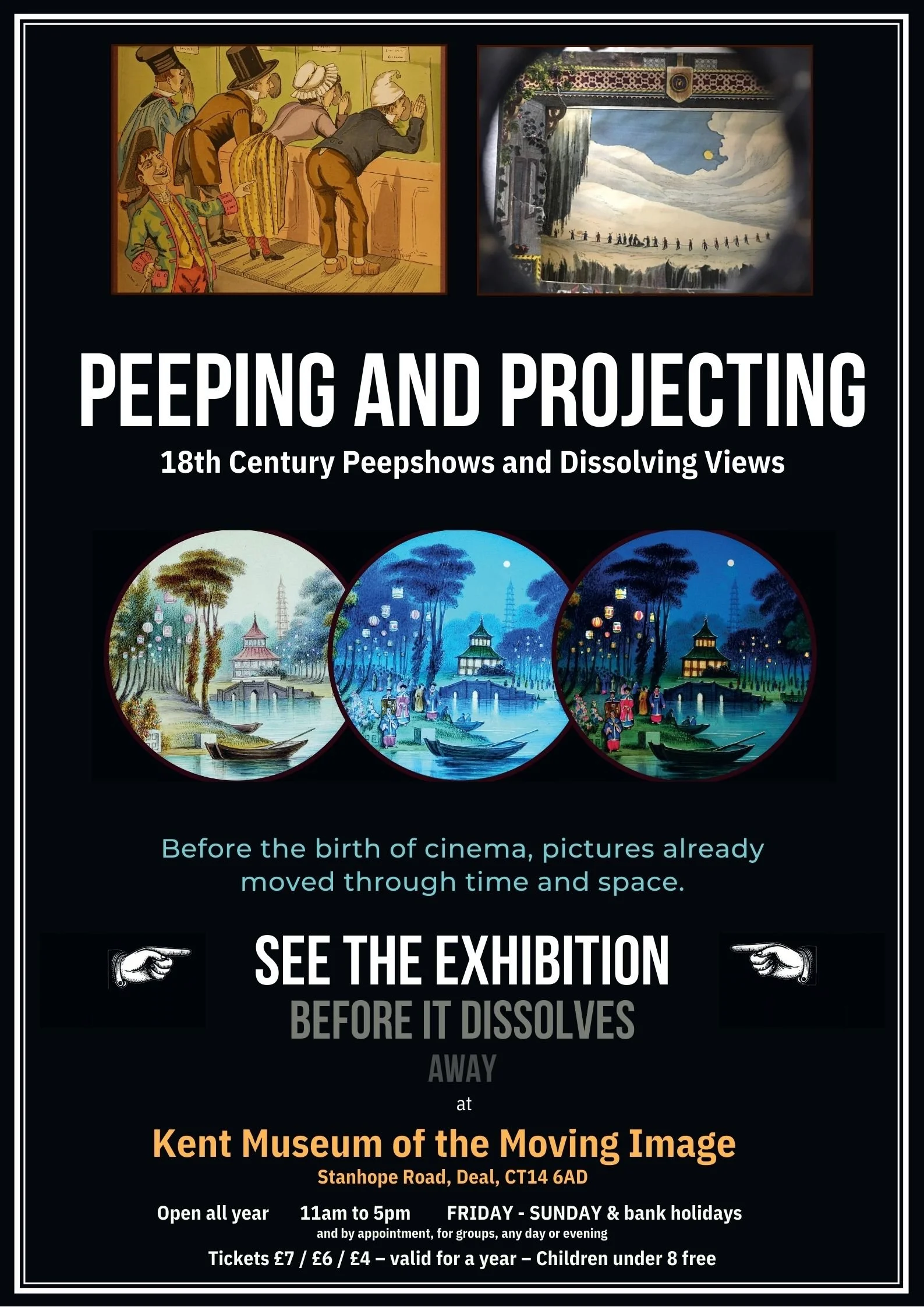

In Susan's Room is a new exhibition about 18th-century peepshow and magic lanterns, Peeping v. Projecting: Victorian Super-Spectacle. (Vinten cameras will return!)

Production Design: Film’s Most Invisible Art

The Terence Marsh Gallery

Autum 2025 brings a significant new exhibition – Production Design: Film’s Most Invisible Art, featuring unique and rare original and donated materials from Oscar-winning designer Terence Marsh (the curator’s father), his mentor John Box, his friends, and his British design contemporaries – who have set a proud mark on Hollywood and worldwide design since the renaissance of the British cinema during and immediately after the Second World War.

A large display cabinet shows in detail the tools and references with which he worked on a variety of films, from Dr Zhivago to The Shawshank Redemption, and includes a painstakingly reconstructed model and design for the famous set of Aqaba in Lawrence of Arabia – designed by John Box and executed by Terence and 300 workers, his first major assignment, aged only 28, and one that demonstrates the fusing of creativity and practicality involved in film design.

The exhibition will be fully installed by October 9th and will expand into sections on the early years of film design, new directions, and Dickens and Film Design over the next two years. The exhibition includes illuminating film clips.

Peeping v. Projecting: Victorian Super-Spectacle

Susan's Room

18th Century Peepshow

Towards the end of the 18th century, developments in perspectival drawing and printing, and the making of lenses, allowed the advent of the “peepshow”, a magic box into which one might look for a view of exotic Venice or far-away Canton. It was a private, interior viewing experience.

Quite different were dissolving views : a public and projected viewing experience, shared with other audience members.

Dissolving Views

We are all familiar with the cinematic “dissolve”. Especially in film noir. The detective uncovers a clue, and the image on screen seems to melt. We see the ruined house as it was in its heyday, or a lost lover emerges, out of the misty past. It is a suggestive and powerful technique.

But before the cinematic dissolve came the magic-lantern “dissolving view”, achieved during projection itself, as the light in one lantern was stopped down, and the light in another brought up.

There is disagreement about when “dissolving views” originated. Possibly as early as 1804. But we do know they were produced in 1827 by the painter and lanternist Henry Langdon Childe, whose finale to a show in March of that year included “the eruption of Vesuvius, storm with shipwreck, [and] mill scene with the effect of a rainbow”. Courtesy of new-fangled “limelight”, the effect was “truly astonishing”.

In the whole 250-year history of the lantern before the advent of cinema, in 1895, there was nothing so enduringly popular and impressive. Dissolving views – in full colour, often dramatised by music and sound effects – helped the lantern endure through the 1920s, well into the cinema era.

World War One on Film and in the Media:

Representation & Remembrance, Art & Authenticity

On the first and ground floors

Of all the means by which we remember World War I, none has proven as powerful as movies – "Animated Pictures", as they once were known, that is, still images that seem to move. Like photographs, cinematic images are traces of reality. Unlike language, they have no past or future tenses. Remembrance on film can thus feel like resurrection: making present, bringing back to life. But cinematic remembrance is only and also a form of representation; and the authenticity we seek in the films of World War One is always mediated by art.

This exhibition has three objectives.

First, to understand how cinema represented WWI – both during the war, when the medium itself came of age, and after the war, in documentaries and fiction films.

Second, to understand how the war impacted the cinema, pushing it to new heights of technical and imaginative achievement, and installing a new world order of national cinemas.

Third, to understand what cinema did and could not do, compared to other media.

The exhibition tells its stories through: cinema and other posters; film clips; film stills, production photographs, fan photos, programmes, pressbooks, and business correspondence; illustrated magazines; photographs, postcards and stereocards; lantern slides; authentic WWI uniforms used in famous films; and original artefacts, like an aviation stuntman's golden helmets and a Moy & Bastie camera used to film battles on the Western Front.

Don't miss the British officers' "dugout", filled with items of entertainment and distraction, or "Comedy Corner", in which Charlie Chaplin figures in surprising ways.

Passport to Ealing: The Films and Their Posters, 1938-1958

The Terence Marsh Gallery and adjoining rooms

At Ealing Studios, in the Balcon era, 1938-1958, all the forces that might make great British films and great poster art converged:

Michael Balcon, a producer at the height of his powers, determined "to project Britain and the British character" to the world ...

the talented directors, writers, cameramen and editors from the free-war documentary and feature film industries who thrashed out ideas at the Studio's famous round table ...

the Studio itself, intimate and friendly, with a bee hive in its rose garden, and the Red Lion pub handily opposite ...

a studio publicist of genius and a well-connected art director, who were given the unique mandate to commission from the best artists of the day ...

the artists themselves, who came to Ealing posters and pamphlets as war artists, illustrators, painters, print-makers, and typographers …

a window of opportunity, when war and its aftermath suspended (temporarily) American domination of British cinema screens, and home-made films that "begged to differ" (temporarily) prospered.

35,000 Years to Catch a Shadow: A Reflective Exhibition

The Margaret Amaral Gallery

Pagans and Christians, primitives and moderns, scientists and artists: for as long as we have been human, we have been intrigued by the phenomenon of the Shadow. The Shadow marks a passage of time. It confers identity ad self-consciousness. But it is also a warning of our destiny: that we are as fleeting and as insubstantial as Shadows. The Shadow is near the root of all mythology, folktale, and religious belief. It falls across the origin of Art.

Deep in caves, about 35,000 B.C., early men drew a magical world of mimic images: Shadows of horses and bison and deer. Greek tradition finds the origin of painting in the story of Kora or Sicyon: grieving to lose her lover, she traced his Shadow on the wall. For hundreds of years, in Java, Indonesia, India, and Turkey, Shadow Puppets have told and retold heroic and comic tales.

In the modern age of Enlightenment and Reason, Science encountered, reshaped, and fell in love with the Shadow. The Silhouette, the Photograph, the Moving Picture: all are Arts and Technologies of the Shadow.

And those technologies begat styles and genres: the Portrait and the Carte-de-Visite; the Horror Film and Expressionism; Cartoons and Silhouette Films; film noir and its shadowy acts of deception, detection, and death.

This exhibition traces the History of Shadows. In doing should, it asks to engage both with the deep History of Cinema and with the History of Representation itself.

OFF-SCREEN

Previous Exhibitions

Passport to Ealing: The Films and Their Posters, 1938-1958

At Ealing Studios, in the Balcon era, 1938-1958, all the forces that might make great British films and great poster art converged:

Michael Balcon, a producer at the height of his powers, determined "to project Britain and the British character" to the world ...

the talented directors, writers, cameramen and editors from the free-war documentary and feature film industries who thrashed out ideas at the Studio's famous round table ...

the Studio itself, intimate and friendly, with a bee hive in its rose garden, and the Red Lion pub handily opposite ...

a studio publicist of genius and a well-connected art director, who were given the unique mandate to commission from the best artists of the day ...

the artists themselves, who came to Ealing posters and pamphlets as war artists, illustrators, painters, print-makers, and typographers …

a window of opportunity, when war and its aftermath suspended (temporarily) American domination of British cinema screens, and home-made films that "begged to differ" (temporarily) prospered.

Farewell to our Royal Polytechnic exhibition!

We have just taken down the first of our original exhibitions. We weren’t sure how our visitors would respond to this in-depth examination of one of the Victorian era’s most fascinating organisations, virtually forgotten until two recent books, Brenda Weedon’s The Education of the Eye and Jeremy Brooker’s The Temple of Minerva, looked at the way it used the projection of images to educate and amuse the general public. Fortunately, our fears were unfounded and the exhibition inspired many interesting and challenging questions.

It was through my interest in the magic lantern that I first learnt about the Polytechnic’s purpose-built optical theatre, its remarkable slide presentations (using no fewer than six huge magic lanterns) and "Pepper’s Ghost". If you missed the exhibition, you can see the exhibition's information boards (beautifully designed by Neal Potter, and incorporating many original images) and the exhibition film showing animated slides as they would have been seen on the Polytechnic screen (expertly edited by volunteer Kevin Shea) below. If there is enough demand, once we have our new exhibition installed, we will put up individual note sheets prepared for the different sections of the Polytechnic exhibition, and digital images of the exhibits.

Our thanks to all who contributed to this exhibition, (besides Neal and Kev), not least volunteer Julie Settle, our ingenious building manager Stuart Moore, and magic lanternist Lester Smith.

David Francis, July 2020

The Royal Polytechnic Institution and Multi-Media Victorian London

The Front Room

19th-century London had doubled in size every decade. The "Monster City" and its restless hordes demanded entertainment. Up sprang the West End—and the extraordinary visual experiences of the Panorama, the Diorama, and the Colosseum.

In 1838, a multimedia palace called the "Polytechnic Institution" joined the list, outdoing its rivals with magnificent "dissolving views"—giant lantern slide images that moved spectators through space and time—in the world's first purpose-built projection theatre, the ancestor of all cinemas. Londoners and visitors flocked to the Poly, by the new train and omnibus—the first generation also to see illustrated newspapers, photographs, 3-D stereoscopes, kaleidoscopes, and the host of Victorian optical toys.

This exhibition use original artefacts to tell this dynamic story. Don't forget to push the Button and see the Ghost!